It may not start a new war. But it will make it much harder to stop an old one.

There, the air forces of countries such as the United States, Russia, Turkey, and Syria are all regularly conducting strikes, often at cross-purposes. And there, on Tuesday, Turkish fighter jets shot down a Russian warplane for allegedly violating Turkey’s airspace. As my colleague Marina Koren notes, the episode marks the first time a NATO country has downed a Russian plane in 63 years.

It’s the kind of incident that has haunted military planners: a tussle between major powers involved in Syria’s kaleidoscopic conflict, with the potential to draw allies into a much bigger war.

But the more pressing problem is arguably the impact the clash could have within Syria itself. After all, NATO countries have been reluctant to invoke Article 5 of their treaty, which commits members to collective defense (the principle was not applied, for example, when Syria brought down a Turkish jet in 2012). And while American officials have publicly defended Turkey’s right to police its airspace, they’ve less publicly been frustrated for months now with Turkey as a partner in fighting ISIS and resolving the Syrian Civil War. Plus, as New York University’s Mark Galeotti observed on Tuesday, “Russia cannot fight hot diplomatic wars on too many fronts, and Europe clearly wants Moscow to be part of the solution in Syria and maybe Ukraine, too.”

Instead, Tuesday’s skirmish threatens to derail international negotiations over Syria just when they seemed to be making (very tentative) progress toward a diplomatic solution to the civil war, and thereby a response to its many symptoms, including the ascendancy of ISIS.

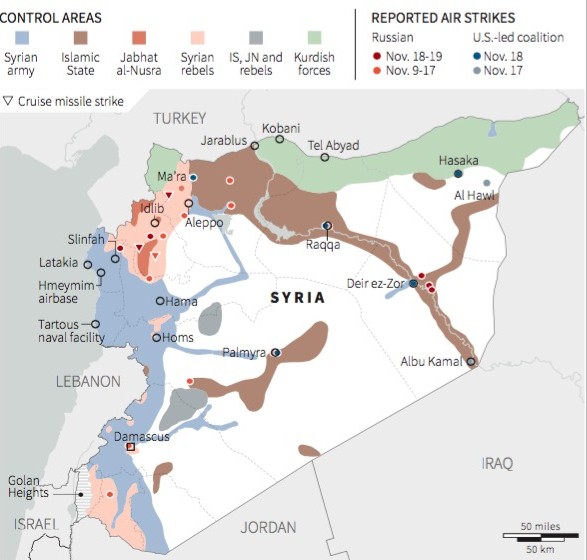

Turkey and Russia have long been on opposite sides of the Syrian Civil War, with Russia supporting President Bashar al-Assad and Turkey backing an array of rebel groups. But these tensions have intensified since Turkey joined the U.S.-led air campaign against ISIS over the summer (while simultaneously bombing U.S.-supported Kurdish militants in the region) and Russia began air strikes in Syria against ISIS and other anti-Assad groups in September.

Many of Russia’s strikes have occurred near the southern tip of Turkey where the Russian plane was hit this week, as the map below indicates.

Recent Russian and U.S.-Led Air Strikes in Syria

Russian aircraft repeatedly veered into Turkish airspace in October, prompting Turkey’s president to threaten a reduction in the country’s considerable and growing commercial relations with Russia, and NATO’s secretary-general to float the idea of deploying troops to defend Turkey. More recently, Turkish officials have been incensed by Russia’s bombing of Syrian Turkmen, a minority ethnic group of Turkish descent, in northern Syria. (In fact, it was Turkmen rebels—who, with Turkish support, are fighting Assad’s forces—who claimed to have killed the Russian pilot who died while parachuting into Syria on Tuesday, after the Turkish military struck his plane.)

Some have speculated that Russia’s incursions into Turkish airspace have not been accidental, but rather deliberate efforts to test Turkey, NATO, and the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition—and their vision for Syria’s Assad-less future. That vision includes the creation of safe zones in northwestern Syria, the very region where Russian bombers are most active.

In recent weeks, however, ISIS’s bombing of a Russian airliner over Egypt and attacks in Paris, among other developments, had given new impetus to diplomatic negotiations over Syria’s civil war. The Washington Post’s David Ignatius reported last week that talks between the major powers in the conflict—the United States, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, and several European countries—were making surprising progress, and that the next stage could feature a ceasefire between Assad and the more moderate rebel groups.

But Ignatius added that there was a possible snag involving whether to include the rebel group Ahrar al-Sham, which has reportedly collaborated with other elements of the Turkey-supported opposition, including Syrian Turkmen fighters:

A test of the delicate process will be whether it includes an Islamist opposition group called Ahrar al-Sham. This rebel group has been backed by Turkey, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, and it has fought alongside [the al-Qaeda-affiliated] Jabhat al-Nusra against the regime and its Russia ally.

If the proxy war between Russia and Turkey intensifies, it could impede progress on compromises like these, which would be critical for reaching any semblance of a peace deal in Syria. And continued Russian and Turkish succor for their preferred factions will likely only prolong the civil war. In 2013, for example, The Economist reflected on the pivotal role foreign powers play in sustaining conflicts such as Syria’s:

So far, nothing has done more to end the world’s hot little wars than winding up its big cold one. From 1945 to 1989 the number of civil wars rose by leaps and bounds, as America and the Soviet Union fuelled internecine fighting in weak young states, either to gain advantage or to stop the other doing so. By the end of the period, civil war afflicted 18% of the world’s nations, according to the tally kept by the Centre for the Study of Civil War, established at the Peace Research Institute Oslo, a decade ago. When the cold war ended, the two enemies stopped most of their sponsorship of foreign proxies, and without it, the combatants folded. More conflicts ended in the 15 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall than in the preceding half-century (see chart 1). The proportion of countries fighting civil wars had declined to about 12% by 1995. ...The main reason for jaw-jaw outpacing war-war is a change in the nature of outside involvement. In the Cold War neither of the superpowers was keen to back down; both would frequently fund their faction for as long as it took. Today outside backers are less likely to have the resources for such commitment. And in many cases, outsiders are taking an active interest in stopping civil wars.

Civil wars, James Fearon and David Laitin wrote in 2008, channeling the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, can be thought of as “international politics by other means.” Before a Russian warplane hurtled to the ground in Syria on Tuesday, there had been signs, however small, that key powers were at last truly interested in stopping Syria’s civil war through politics. Now, however, they

No comments:

Post a Comment